- SY-1000 Expression Pedal Shoot Out! Comparing the Roland EV-5, Boss EV-30, Moog EP-3 and Mission Engineering SP-1

- SBC-1324 New Videos Posted!

- BX-13 Do-It-Yourself Cooper tracing and silk screen available for download.

- Roland Centerstage - Roland Makes !t Happen! 1984 Winter Namm - First time ever!

- Boss SY-1000 All About Program and Bank Change Commands - Boss SY-1000 Webpage

- Boss SY-1000 All About Program and Bank Change Commands YouTube Video

- Email Blast Archive! 4 Years Plus of Email Blasts Archived.

- Roland BC-13 Full review on YouTube

- NEW Interior Photos - First time ever!

- The Most Requested GR-700 Patch A breakdown of how to recreate the classic Roland GR-700 Factory Patch 3-5, "Lead II" as used by Glen Tipton of Judas Priest, adding a signature sound to the excellent track 'Turbo Lover'.

- High Res PG-200 Manual (NEW) NEW! I tracked down a mint PG-200 Owner's Manual, newly posted.

- Roland GR-500 MINT Stunning Photos As seen on Reverb! A really stunning example of a Mint Roland GR-500/GS-500 combination. Includes the very, very rare GR-500 case, never seen before!

- The Swallow's Dream is a performance piece made only using sounds from the Boss SY-1000 with an Epiphone Dove Pro equipped with the Graphtech GHOST Acoustic Steel String Midi Kit.

- Mastering Resynthesis with the SY-1000 This video shows how to record the master stereo output of the SY-1000 in the USB audio to a stereo track. In this way many tracks of guitar synthesizer can be recorded and layered to create a final composition.

- Epiphone Dove Pro with Graphtech GHOST Midi Kit In this video I share a few insights about a Epiphone Dove Studio Acoustic-Electric Guitar Vintage Burst I purchased with the Fishman Sonitone and Sonicore System and the Graphtech GHOST Acoustic Steel String Midi Kit installed.

- Roland GM-70 MIDI Polyphonic Expressions: Using the vintage Roland GM-70 with the Arturia Pigments Soft Synth with MPE MIDI Polyphonic Expressions

- Roland GM-70 Alternate Tunings and MIDI Continuous Controllers: Using the vintage Roland GM-70 alternative tunings, and assigning MIDI continuous controllers

- Roland Hardware GR-700: Vanguard to Synth Frontiers: Announcing the Roland GR-700! From the Roland Users Group, Volume 2, Number 4

- Boss SY-1000 On The Run Sequence - Step By Step Tutorial - EMS Synthi AKS - Analog Recreation: This is a step-by-step tutorial showing how to recreate the famous 'On The Run' sequence from Pink Floyd's album The Dark Side of the Moon.

- Boss SY-1000 Guitar Synthesizer Sequence Step By Step Dynamic Synth Tutorial: Tutorial on using the Sequencer in the Boss SY-1000.

- Jeff Baxter - How I Became An Electronic Musician: Read this interview with guitarist Jeff Baxter from the first issue of the Roland User's Group Magazine.

- Boss SY-1000: Resynthesis - YouTube Video: Multitrack Guitar Synthesis Recording

- Boss SY-1000 Reaktor 6 - DIY Build Your Own Guitar Synth YouTube Video: Use Reaktor with the Boss SY-1000 to build your own software guitar synthesizer.

- Korg MS-03 Forget MIDI! Forget the Hex Pickup! Direct Guitar to Analog Synthesizer with the mighty Korg MS-03 and the Arp Odyssey and Behringer K-2 (Korg MS-20)

- Korg MS-03 Video - Demo of the RareKorg MS-03 with the (Korg) Arp Odyssey and the Behringer K-2 (MS-20 Clone)

- Roland SPV-355 Guitar to Synthesizer Video - Roland G-303 Direct to the Roland SPV-355

- Behringer K-2 Guitar to Synthesizer Video - The hidden Guitar Synthesizer in the Behinger K2!

- GR-700 Tech Tips from Roland! Originally published in the Roland User Group magazine, Volume 2, Number 4.

- GR-700 Performance Tips! Originally published in the Roland User Group magazine, Volume 3, Number 3.

- Guitar Greats and the GR-700 Originally published in the Roland User Group magazine, Volume 2, Number 3.

- Roland Hardware - GR-700 G-707 Originally published in the Roland User Group magazine, Volume 2, Number 3.

- Synth Ethics Featuring the Roland GR-700 Tips on using the GR-700 from Mark Wood, Guitarist Magazine May 1985

- Three Favorite GR-700 Patches By Steve Carnelli, Guitar PLayer June 1986.

- Roland GR-700 Guitar Synthesizer Product Review By John Themis Guitarist May 1985

- Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays Interview - 1989 Pat and Lyle interviewed during the height of the popularity of the Pat Metheny Group in Music Technology Magazine.

- Pat Metheny Interview - 1985 Vintage interview from the era of 'First Circle', and 'The Falcon And The Snowman' - Guitarist Magazine

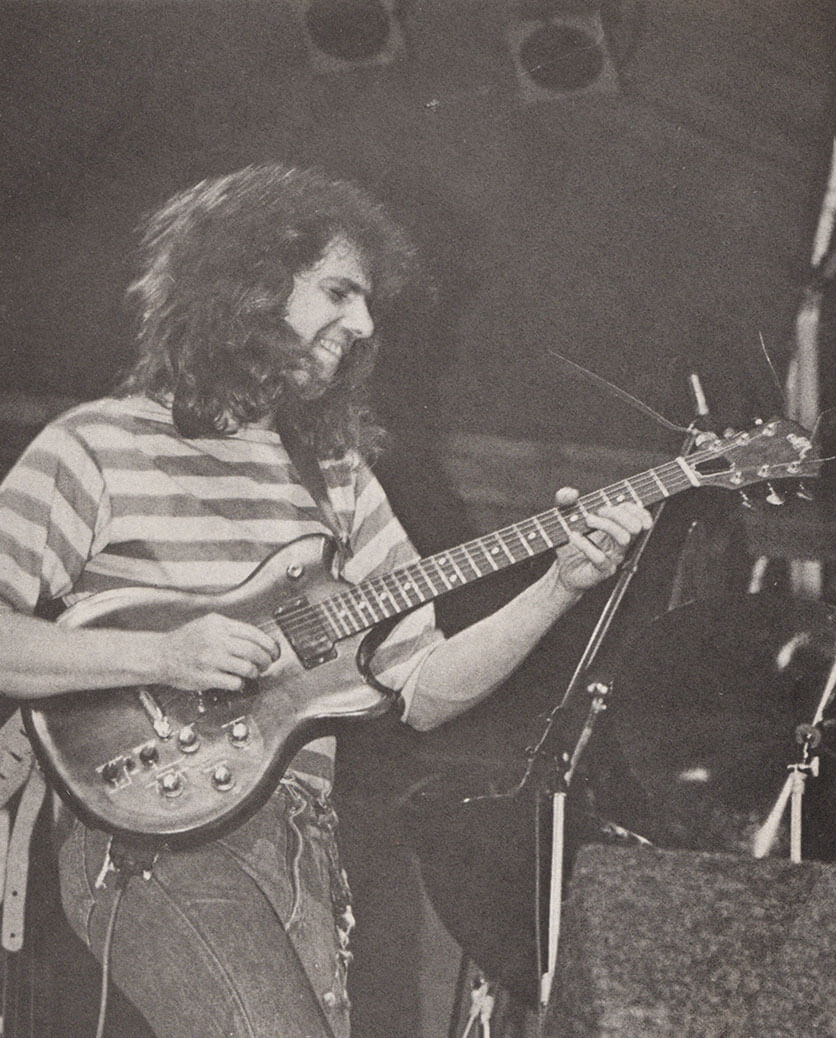

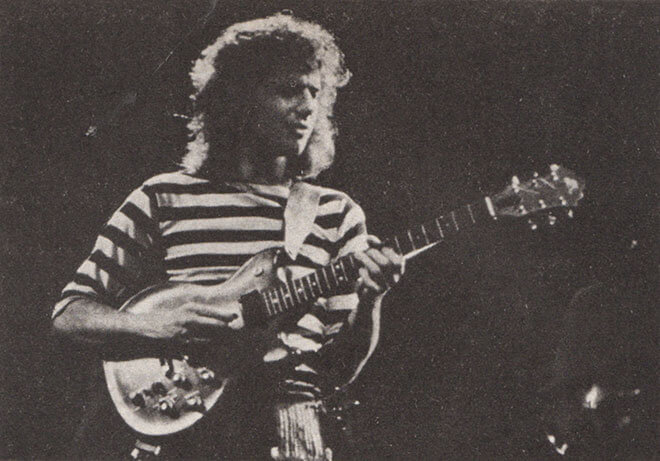

- Pat Metheny Interview - 1984 Vintage interview from the Roland Users Group covering Pat's early career as musician and highlighting the Roland GR-300.

- Boss SY-1000 Recreating the Pat Metheny GR-300 Solo Sound YouTube Video detailing tweaks to recreate the dramatic Pat Metheny GR-300 solo sound with the Boss SY-1000.

- Pat Metheny - New England Digital Synclavier Demonstration YouTube Video Old Grey Whistle Test - Roland G-303

- Pat Metheny with NED Synclavier Prototype YouTube Video Early Guitar Synthesizer Controller

- Pat Metheny and the NED Synclavier Read Pat's notes on using guitar synthesizers and the New England Digital Synclavier.

- Van Halen Michael Anthony Roland GR-33B G-33 Bass Guitar Synthesizer Solo YouTube Video From 1982 Largo and 1983 Devore In Concert Live Performance! FILTER SWEEPS!!! DELAYS!!!

- Spicetone 6Appeal Guitar Processor Analog Hexaphonic Distortion Pedal The Spicetone 6Appeal is a modern take on the poly distortion, hexaphonic (hex) fuzz pedal.

- GR-100 GR-300 Power Supply Repair New video on the one GR-100 or GR-300 or GR-33B power supply mod you MUST do!

- Roland GR-D Interior Photos: First time on the web! Interior photos of the Roland GR-D!

- Gibson Les Paul Custom LPK-1 Repair In depth step-by-step repair of the Gibson Les Paul with LPK-1 kit.

- Roland G-303 A Fresh Look! Trevor Harley sent me these photos of his Roland G-303. The guitar was refinished with a flame maple top and back by the Canadian Luthier George Furlanetto. Note that the touch pads have been relocated below the bridge pickup.

- Steinberger Time! Newly posted photos of a White Steinberger GL-4T-GR

- Ultimate 24-Pin Custom Guitar Stunning photos of the most amazing custom built 24-pin guitar ever made! The solar system on the fret board and more!

- More PINK Please! Hamer Phantom A7 Nothing says vintage 80s guitar styles link a solid pin finish! Samuel Cuevas sent me a few photos of this very, very rare pink Hamer Phantom A7 Roland-Ready guitar.

- Boss SY-1000 with Roland G-33 YouTube video with a demonstration of all 200 Bass patches for the SY-1000

- BAK-1 Videos A new video on the BAK-1 Electronics card, plus comparison of the G-88 and G-77 electronics

- BAK-1 Photos Newly posted photos of the BAK-1 Bass Guitar Synthesizer Installation Kit

- Roland G-33 G-88 G-77 BAK-1 Vintage Analog Bass Guitar Controller Assembly - Comparison

- G-77 Fretless First time on the web! New photos from Skylark of his pristine G-77 Fretless bass.

- Clone 24-Pin Cable At long last there is a quality clone of the impossible to find Roland 24-pin cable. This is a quality, made in the U.S.A. cable produced by 'MagicTrashMan' in North Carolina. Check out the description and video on the cables page.

- Roland GR-500 Mods - Part 1 Thanks to the Phantastic Jimi Photon who pointed me to the March April 1981 Polyphony magazine with the first list of Roland GR-500 modifications.

- Boss SY-1000 All Bass Patches! Complete on YouTube (no talking)!

- Read The Full Interview The year was 1983, and the Police were exploding on the charts. The inventive and adventurous Andy Summers was busy rewriting what a rock guitar player could be. The smash hit "Don't Stand So Close To Me" prominently featured the Roland GR-300, played by Andy with the Roland G-808. Volume 2, number 2, of the Roland Users Group magazine featured a great interview with Andy, reproduced for the first time on the web!

- Read The Full Review Roland shifts direction in 1987, releasing the Roland GK-1 and GM-70. This combo said goodbye to Roland guitars and dedicated guitar synthesizers like the GR-300 and G-808 in favor of a system that could be mounted on any guitar, and used to control any MIDI synthesizer. Read Warren Sirota's review of the GK-1, GM-70, and the MKS-50 and MKS-70.

- Roland GR-500 Mods and Tips! Electronic Musician magazine started life as Polyphony magazine, edited by young writer named Craig Anderton. Seemingly produced by on a single typewriter in the early eighties, this Polyphony article features insights and modifications for the Roland GR-500!

- History of the Guitar Synthesizer Travel back in time, before MIDI, before the Roland GR-700, to the early 1980s, when the Roland GR-300 was the pinnacle of guitar synthesizer technology.

- Steve Howe and Steve Hackett Prog Rock Guitar Titans Teamed up for GTR, Chart-Topping Band Centered around the Roland GR-700!

- Steve Howe Roland Profile A detailed profile of Steve Howe, his Roland G-505 and GR-700 from the 1984 Roland Users Group Magazine

- Boss SY-1000 Tutorial Videos New vidoes on setting up Guitar-To-Midi and blending normal guitar sounds with modeled sounds.

- Washburn JB100 Profile A look at the Washburn Roland-Ready JB100. Detailed photos and videos!

- Lyle Mays Remembering Lyle Mays - New YouTube Playlist with Unreleased Tracks from live Radio Broadcast

- Boss SY-1000 Interior Photos and Unboxing Photos

- Parker NiteFly SA with Factory Internal GK-2A Just Added! A profile of a Parker NiteFly SA with factory Roland GK-2A. Demos with Roland GR-100, GR-300 and GR-700.

- Behringer Deep Mind 12 The New Roland GR-700? Vintage Sounds in a Modern Analog Synth

- GR-300 Case Rare spotting of the Original Roland GR-300 Case!

- Roland Ready Les Paul Photos of Bob Welch's Custom Shop Les Paul Paul with Roland electronics.

- Peter Frampton With Roland G-303 Thank you Eric Fisher for finding this rare live video!

- Picture This 30th Anniversary Release - Wayne Scott Jones Album from November 1989.

- Converting the M-16C into an M-64C - Detailed tips on converting the M-16C into a M-64C with four times the memory capacity!

- Roland G-33 Major Update! 18 new photos, PLUS 4 YouTube videos!

- Switch Roland-Ready MIDI Guitar Complete details on the Switch Wild-IV, PLUS all the Switch Guitars!

- Boss GP-10 and Hex Fuzz Details on great hex fuzz sounds from the Boss GP-10

- Steve Hackett - Roland GR-500/GS-500 Performance - Please Don't Touch From the 'Please Don't Touch' tour, November 8, 1978. Great GR-500 showcase!

- Vintage Roland GR-300 Review from Electronics & Music Maker - Nov 1981

- Roland GR-77B for Reaktor - Download a modeled Roland GR-77B for Native Instruments Reaktor 5!

- Roland GR-700 Blue - Remake with 'GR-300' blue finish, new handles, and handsome natural wood end blocks! Thank you Chuck Nin!

- PG-200 - Updated NOS New-Old-Stock photos of the Roland PG-700, programmer for the Roland GR-700. Thank you Eric Rusack!

- G-707 White Ever wonder what a G-707 would look like redone in a brilliant white finish? With Steinberger folding leg rest!

- 3D Printing Vintage Roland Guitar Parts - 24-to-25 pin Plate - Courtesy of Jusin Casey

- David Gilmour - Solo with Roland STK-1 and GR-700!

- Moog Voyager XL (with Casio MG-510 Cameo) Space Music - Melodic Downtempo, Ambient, Ambient& PsyChill Mix.

- Roland GM-70 Guitar-to-MIDI Converter - Review by Paul White, Music Technology Magazine, April 1987

- Theme from M*A*S*H. Arranged using only the ARP Odyssey for all sounds, synths, drums, efx, etc.

- Ibanez IMG2010 - Owned by George Benson. Rare 'Endorsee' finish with Silver hardware.

- Arp Avatar Review by Paddy Kingsland. Vintage review of one of the very first analog guitar synthesizers, the Arp Avatar - Competitor to the Roland GR/GS-500.

- 24-to-25 Pin Mounting Plate. You can download the newly posted '24-25.dxf' CAD file to make your own 24 to 25 pin mouting plate. I used the company Big Blue Saw to make my 24-to-25 plates from aluminum. The price for a single piece can be expensive, but if you order in quatity the price will drop considerably. Plus, they have specials from time to time!

- Roland GR-100 Samples Sounds. The Roland GR-100 Owner's Manual has a list of "Factory Presets", Sample Sounds, at the end of the Owner's Manual. These sample sounds were intending to give some direction on how to use the GR-100, using features such as Filter Modulation, Chorus, and Vibrato, all served up with the classic hex fuzz sound the GR-100 is famous for. Check out this new YouTube video I posted which goes through the Sample Sounds to get a little flavor of what this vintage 'electronic guitar' synth sounded like!

-

SBC-1324 Roland 24 or 13 Pin Input to 13 and 24 Pin Output

Back in 2009 I was approached by a very talented Canadian guitarist who wanted to be able to control both vintage Roland 24 pin GR-series synthesizers and modern Roland 13 pin GK-series synthesizers with one guitar, either a 13 or 24 pin guitar.

The SBC-1324 is the unit I built to meet this need. The unit has both 13 and 24 pin inputs, and a master analog switch to select between the two. There are six amplifiers for each string input, used primarily to boost the 13 pin signals to the 24 pin format, but they can also be used individually to amplify any single string input, whether 13 or 24 pin.

-

Artist Highlight: Neal Schon

Journey guitarist Neal Schon was frequently seen in the early eighties playing a Roland G-505 guitar paired with the GR-300. Schon is not usually thought of as a 'Strat' player, much less a guitar synthesist, but he makes great use of the G-505/GR-300. An outstanding track is the tune 'Valley of the Kings', using the 'Duet' mode of the GR-300.

- Roland SIP-300 Fresh Photos! Super clean photos from an auction by Tone Tweakers.

- Roland GR-300 Emulation with Kontakt 5 or Roland SR-JV80-04 / SRX-04 Ultimate Keys / INTEGRA-7. Download a complete Kontakt 5 patch and trigger a GR-300 with MIDI! Or check out a demo of the Roland GR-300 patch created by the legendary Scott Summers.

- UX-20 - 13-Pin Splitter/Distributor with Buffered Guitar Input Schematic

- Pat Metheny writes about on using the NED Synclavier Digital Guitar Option - First Time Online! From the 1984 NED Owner's Manual.

- Steinberger XL2-GR Guitar Synthesizer Controller - Vintage Roland Ready Bass Guitar Synthesizer Controller

- Pedulla MVP-S Guitar Synthesizer Controller - The phantom Roland Ready Guitar Synth Controller!

- GK QuadBox Schematic Build your own GK QuadBox, 1 input, 4 output 13-pin Guitar Synth Signal Distributor - Combined US-20 and GKP-4 clone!

- RC-1324-VR Roland 13-in to 24-pin Converter Detailed schematic on the acclaimed RC-1324. Control vintage 24-pin Roland guitar synths like the GR-700 and GR-300 with modern 13-pin controllers like the GK-3, GK-2A or the Godin series of guitar controllers

- Modulus Graphite Blackknife Special Guitar Synthesizer Controller

- Roland GR-700 Operating System Upgrade New Sounds! Faster Response!!

- Do-It-Yourself DIY Roland and Ibanez Guitar Synthesizer Control Panel Overlays

- The summer NAMM 1985 show was the year when MIDI became accepted as a standard across the industry, and guitar manufacturers unleased a variety of MIDI guitar products not seen since. From Roland to Steinberger to Ibanez to the ultra rare Octave-Plateau Voyetra MIDI guitar, MIDI was everywhere.

- Detailed information on the vintage IBM-PC music production software from Voyetra. Voyetra is the same company that produced the Kat and Kitten analog synthesiers, the ground-breaking Voyetra Eight polyphonic analog synthesizer, and the ultra rare Octave-Plateau Voyetra MIDI guitar.

- WBRA Public Television Music Video featuring Wayne Joness using Voyetra Sequencer Plus - Live Performance.

- Vintage Interview with Jazz Fusion pioneer John McLaughlin about using the Roland G-303 guitar synth controller and the New England Digital Synclavier with Digital Guitar Option

- Details on the amazing Synclavier II Digital Guitar

- East Side West Side by John McLaughlin From the Album Mahavishnu - Transcribed by Steve Vai.

- Vintage 1980 Full Page Roland G-808 Advertisement featuring Bernie Marsden (Whitesnake) - Who knew? Hard rock icon Bernie Marsden with a Roland G-808!

-

Gibson Custom Shop Les Paul "Studio Custom" Roland Ready Synthesizer Controller Update

More pictures on the Gibson Custom Shop Les Paul Roland Ready Synthesizer Controller page, plus an update on the number of models built. - Musico Resynator | Hexsynator - 1980s Pitch and Envelope Tracking Synthesizer with Roland 24-pin Guitar Synthesizer Input - Detailed photo gallery from November 2017 fundraiser at Sound City Studios in Van Nuys, CA.

-

Gibson Custom Shop Les Paul "Studio Custom" Roland Ready Synthesizer Controller

Beyond the standard Roland offerings in the G-X0X series, there are vintage 24-pin Roland-Ready guitars for just about every niche: the Hard Rock Hamer A7, the traditional player's Zion Strat, or the cutting edge Steinberger GL-2T/GR.

But the classic, eternal, "Cadillac" of the series has got to be the Limited Edition 1985 Gibson Custom Shop Les Paul with the Roland LPK-1 Electronics. Every guitar was the product of Gibson's acclaimed Custom Shop in Kalamazoo, Michigan. Kalamazoo made Gibson Les Pauls have been called the 'Holy Grail' of electric guitars. These vintage guitars combine all the craft and musicality with the feature-rich Roland LPK-1 electronics package, the same electronics found in the G-303 or G-808 guitars. - Jazz and the GR-50! Acclaimed Jazz Guitarist Brad Rabuchin rocks the Roland GR-50 in this track 39 Steps: A Spacewalk. This is Space Station MIR, a collaboration with Flugelhorn Horn genius and composer Michael Wetherwax, with Wayne Joness on keyboards and programming. Watch Now on YouTube.

- BX-13 Micro Schematics Yes! At long last! The final schematic for the BX-13 Micro is available on the website! This design incorporates a VCA (voltage controlled amplifier) with an option to select either guitar or hex fuzz as the guitar signal, plus using controller 2 (resonance) as secondary control source acting as a EV-5 pedal.

- At long last the Vintage Roland Guitar Synthesizer Resource site has a full profile on the Steinberger GL-2T/GR Guitar Synthesizer Controller, with unseen schematics, photos and video, with additional information on the GL-3T/GR and GL-4T/GR.

- Musico Resynator | Hexsynator - 1980s Pitch and Envelope Tracking Synthesizer with Roland 24-pin Guitar Synthesizer Input.

- Korg Z3 Patch Editor Adaption for the Korg Z3 - Thanks to Korg Z3 user David for this free software download.

- GS-500 Video Playlist featuring Terje Rypdal - Luc Bertels hipped me to videos of Terje Rypdal using the Roland GR-500 and GS-500.

- Roland GR-700 and GR-77B AB-700 Case - Image gallery with 12 photos of the rare official Roland factory road case.

- Xotica EA-1 with Roland Ready Guitar Graph Tech Ghost Pickups - Detailed information on this very rare, Rland ready 13-pin Acoustic/Electric Roland guitar synthesizer controller.

- Factory Blue Roland GS-500 - Last year while visiting Japan I stumbled upon a factory BLUE Roland GS-500 in a Tokyo music store! Check out the exclusive photos published for the first time.

- Sounds of the GR-77B! New video posted featuring a layered bass combination of the Roland MKS-70 (same sound engine as the GR-77B) and the GR-77B.

- Pat Metheny Extended Interview - I tracked down the original Guitarist Magazine, May 1985, and have posted the complete interview with Pat Metheny. The previous interview was an abbreviated version.

- GR-300 Synthcheck - A detailed 2000 word review from "The Complete Music Magazine", dated November 1980

- Gibson Explorer - Finally! A home for one of the rarer custom Gibson vintage Roland guitar synth controllers

- Jimmy Page - Vintage 1985 magazine ad featuring the guitar legend and his G-707/GR-700 rig!

- LPK-1 Installation Diagram thanks to John Doucette for emailing the scans.

- GK-20 Schematic - 13-pin Guitar Switcher, Schematic ready for download

- Filter/Buffer Schematic - Schematic ready for download.

- Roland GR-700 and GR-77B Updates: From the Roland User Group Archives, a complete MIDI guitar and MIDI bass system profile!

- Roland GR-77B Updates: Finally! The Roland GR-77B and G-77 pages have been updated. Be sure to check out the G-77 page as well.

- Vintage Roland G-505 and GR-300 combination magazine advertisement.

- GR-700 One Step Beyond!: From the 1985 Roland User Group Magazine

- GR-700 4x Memory Expansion!: Easy to do, super DIY Memory Expansion!

- Ibanez IMG2010 and MC1: Updated! High-Res Brochure from 1985

- G-707 Steve Hunter: Vintage Product Review from 1985, Part 2!

- G-707 Steve Hunter: Vintage Product Review from 1985, Part 1

- GR-500 Steve Hackett: Vintage Product Review from 1978!

- GR-500 Patch Sheet: Original Blank Patch Sheet

- GR-500 - Solo Voice Tuning : Adendum on Tuning the Solo Section

- GR-300 Filter Mod: LFO to Filter Modification

- GR-300 Output Mod: Increase the output of your GR-300!

- GR-55 Schematics, Service Notes: Full factory service notes for the Roland GR-55

- Ibanez MIU8: Specs, photos, details on the rarest of rare!

- MIU8 Schematics: Schematics and Service Manual (pdf)!

- Korg Z3 Product Page: From early Product catalog!

- Hamer A7 Guitar: Added to the guitar pages, a tribute to the Hamer Phantom A7! Tubo Lover rocks!

- GR-500 24-pin Connector Change: Documentation of the change from the original, pin-type C24 connector to the much more common C24 positive (locking frame) connector.

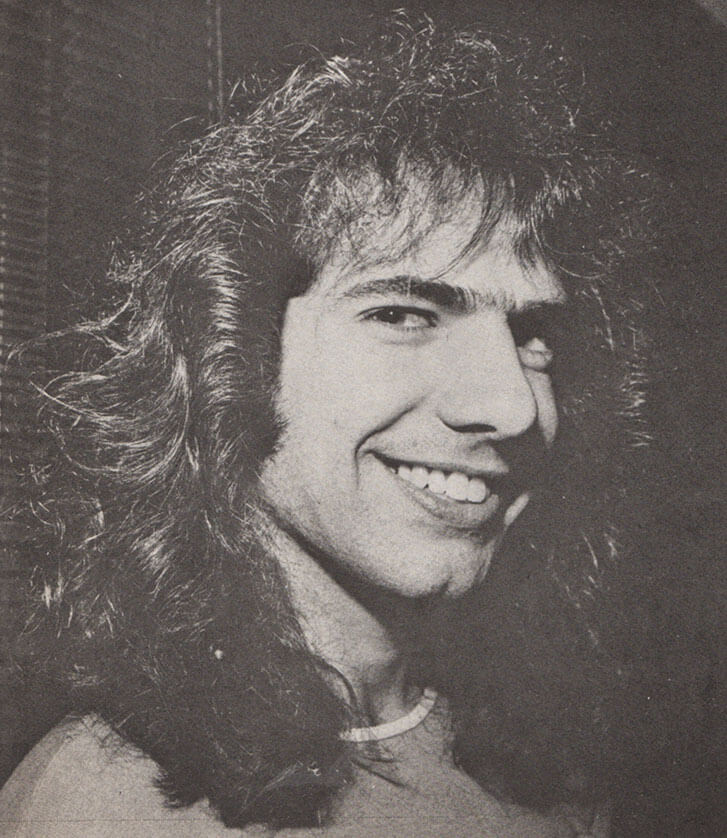

Pat Metheny

by Jess Ellis Knubis

Roland Users Group, Volume 2, Number 4

The sound seems to swell and cascade, echo and scream. Sounds that transcend the boundaries of the guitar yet seem to epitomize everything that the guitar is capable of.

At 29, Pat Metheny has popularized a new era in jazz guitar, taken the instrument outside of its normal parameters in terms of both musical creativity and the creative use of technology.

The unique style, first developed in the bars of Kansas City, has matured over the years through association with such diverse artists as Joni Mitchell, Paul Bley, Charlie Haden, Sonny Rollins, Hubert Laws, and of course, his ubiquitous partner, Lyle Mays.

And that unique sound, first the product of an inexpensive Gibson arch-top and liberal doses of digital delay, has developed into one of the most highly technical combinations of hardware, software, and experimentation in modern improvised music.

Yet through that synthesis and development, there remains the essential articulation, expression, and love of music that continues to excite audiences with the innovation that first brought him acclaim.

In this conversation, Pat discusses his musical development, coping with international success, and the future of synthesized music.

RUG: What sort of music did you hear in Lee's Summit? What was the home environment like?

PM: Well, there was all kinds of music around. Being from that part of country, country and western was real popular. You couldn't go outside and not hear that, so that was part of it. And at the time that I grew up, like most people my age, the rock n roll thing was really starting to hit. When A Hard Days Night came out I think I saw it 14 or 15 times, I guess I would have been 9 years old. And the town I'm from was sort of famous for its marching band community. And also, I lived close enough to Kansas City with the whole jazz scene that was happening there, although it was distant to me until I was 14 or 15. From the time I was 15 on, I was working 7 nights a week in Kansas City with jazz greats. So I was lucky to have a whole bunch of influences and I was always a big fan of all kinds of music.

RUG: Was your family supportive?

PM: There was conflict - especially in the days when I was still going to high school and working in Kansas City in sleezy joints. But as time went on they became more and more supportive and now they're really fans. But I learned to play on the bandstand in those clubs. I was real fortunate that, at the time I was getting active on the Kansas City scene, there were no other guitar players to speak of, one or two other guys and that was it. So I got every gig by default and in fact, found myself with the best gigs in town, with the best players. Not that I was that good, but because there were no other players around at a time when the popular sound in a lot of these places was the organ, guitar and drum trio thing, and I did a lot of that stuff.

RUG: So by that time you were already comfortable playing through changes, you had developed your chops ... ?

PM: Yeah, even from the time I was 15 or 16 I was doing that stuff. The kind of music I was playing around Kansas City, even though I wasn't playing it that well was, you know, pretty complex jazz standards. I mean, I kind of bypassed the whole rock-n-roll thing and went almost immediately into jazz and very avidly, right from the first day practically, I was practicing 10 or 12 hours a day. I was really into it. I was really influenced by Wes Montgomery, Kenny Burrel, Grant Green and Jim Hall. Those were the big four for me, as far as guitar players. Later on I got involved with Jimmy Raney, who was really important to me. And after a certain point, and I think this is true with most people who are looking to be improvisors, I didn't care what instrument it was played on, whether it was guitar players or not. So the big influences for me, after the initial fascination with the guitar were Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman, Sonny Rollins, Herbie Hancock, McCoy Tyner, Bill Evans, you know, all the cats.

RUG: Was joining the Gary Burton group an important development?

PM: As far as national exposure, yeah. Gary was another big favorite of mine and his group at the time was the only one that was using the guitar in a progressive way. Most jazz groups didn't have a guitar at all until 1968 or so when Gary came along.

RUG: When did you first start using the digital delay?

PM: Well, when they first came out. I had an experience in the studio with one and I couldn't afford it until about 1977 and that's when the cheaper ones started coming out. But I was hooked immediately, they just killed me.

RUG: Your formal music education, then, was limited?

PM: Well, even though I never really went to school or went to see a guy in a music store once a week or anything, I was very definitely a student of music. I studied all the jazz manuals, read all the books; even before I left Kansas City, I could analyze any tune and tell you what the resolutions of the harmonies implied in terms of various chord scales and that sort of thing. It's just that I never had an official teacher and had there been teachers around, I'm sure I would've had them. When I was teaching at Berklee as part of the Burton band, I was having to teach certain things that I didn't exactly...well, it was stuff that I knew, but I just had to learn the correct names for and Gary really helped me out on all that stuff.

RUG: Do you recommend a self-taught approach?

PM: In a way, I'm always reluctant to say that I'm self-taught because that implies that you don't really know what you're doing. But I think, if you can do it that way it's better because you're constantly accumulating things and there's never that expectation of what you don't know.

RUG: Is Lyle Mays' background more formal?

PM: No, in fact, our backgrounds are very, very similar. He's also from a very rural town that actually makes the town I'm from look like New York City. He's really from the sticks. We could both analyze to the "nth" degree if we had to and I think that we both felt that was important, even though there wasn't somebody around to show that to us.

RUG: Tell me about the work you're into now, the Synclavier and the Roland Guitar Controller.

PM: Well, it's the most incredibly exciting and magical thing that's probably ever happened. How's that for starters? I first got a Synclavier about 3 1/2 years ago now, and that alone was a major thing for me because it brought everything right under my fingers. Even though I didn't really have the keyboard chops, to be able to have a 16 track sequencer that was efficient and mobile as that sequencer, was compositionally, an incredible breakthrough for me. Everything was possible all of a sudden. So immediately after getting it I started calling them up every day and saying, "Look, we gotta get a guitar interface for this." And over a period of three years and two or three prototypes, a lot of back and forth trips up there, we came up with the idea of using the Roland as a trggering system. Because they were talking about making another guitar with the hex pickup and I mean, really, all I needed was another guitar to get the feel of. And I think the Roland is an excellent guitar, the brown one, the G-303. And so I took that up there (to New England Digital). And they started doing some tests and they said, "Everything we need is right here, let's just use that." And I said "YEAH!". So they started working on it and now any Roland guitar can plug into the interface. I mean, you don't do anything to the guitar, immediately you're into the Synclavier world.

RUG: The Synclavier is kind of an expensive machine....

PM: Yeah.

RUG: Like, $60,000....?

PM: Yeah, well it varies depending on how many voices and options, that kind of thing. But to be accurate, I think that if a guitar player wanted to get in on it and wanted to start with an eight voice system, you could get started for less than $20,000.

RUG: Not cheap by most people's standards.

PM: No, but still, on the other hand, I honestly feel that most people have no idea what we're talking about here. This is a breakthrough that makes the electric guitar look like nothing. It allows guitar players to, first of all, sound like any instrument, to record into a sequencer directly, to play anything, have it printed out in music...not only that but to have a certain feeling as a musician that allows you to get away from the sort of inhibitions that guitar players traditionally have had to deal with. In other words, you can play notes and take your finger off the strings and the note will still ring...stuff like that, that keyboard players have been able to do for a long time now. I mean...I just can't say enough about it. It's the kind of thing where, literally, I get up in the morning, when I'm not on the road, and I sit in there for twenty hours and then go to sleep and then do it again. And you can do that every day, it's wild. Plus, with the Roland AB switcher box (US-2), if you already have a Roland synthesizer, you can plug the guitar into the guitar input and have channel A be the Roland and channel B be the Synclavier and play them both together at the same time.

RUG: The two seem to be completely different instruments.

PM: Oh, definitely. From what I understand, the Synclavier works from pitch to voltage where the Roland uses what they call time to voltage. The Synclavier uses an extremely high-powered computer to read the string like, 50,000 times per second. I mean, you can see on the computer exactly what you're playing as you're playing it.

RUG: You mean as far as pitch and waveform...?

PM: Pitch, what string you played on, how hard you played it, that kind of stuff. The Roland is obviously geared to a much lower price, but to tell you the truth, I mean...I'm not going to throw away my Roland. There are things that it does that my Synclavier can't do, like for instance, sound like a guitar, in the sense that to me, the Roland GR-30Roland GR30 is like a super hot rod guitar, it feels like a guitar, it responds like a guitar, all that stuff, which the Synclavier can do, but the Roland has a certain quality to it. I mean, I don't know much about the circuitry, but it seems to me that it's following the analog part of the sound as opposed to measuring the string, and that's a real advantage for that screaming guitar stuff. (Editor's note: At the time of this interview, Metheny had just received his GR-700 module. He has been using it in Europe and was not available for an interview update.)

RUG: Sort of the ultimate effects device.

PM: Yeah, except I've been constantly surprised over the years by how much further up the ultimate can get. But to have the Roland and the Synclavier from one guitar is a sound that, until you've experienced it, you can't believe. I think Roland should take it as a real compliment, 'cause what this means is that the Roland guitar is going to be the standard. I'm sure that there will be other manufacturers that come out with systems that use that 24 pin connector as the standard language from guitar language. Because, I mean, they've done it, they've come up with a really hip pick-up and a very logical way of accessing it with that kind of cable. Ultimately, I think that the Roland guitar controllers and the whole pick-up system may become, you know, kind of what the magnetic pickup is now, the industry standard.

RUG: Speaking of guitar language, what experiences have you had with the MIDI system?

PM: Well, none so far. In fact, I'm highly skeptical of it, to tell you the truth.

RUG: Why is that?

PM: I know that it moves at a very slow rate, relative to the kind of stuff that we're talking about in the Synclavier. They're talking about one bit every 5 msecs and um, I can imagine, for instance, someone triggering a Synclavier from some other source just to get the Synclavier sounds, but the Synclavier is spitting out like, well, it's a 16 bit machine so like, every 5 msecs there's like hundreds of bits passing, let alone one bit every msec.

RUG: You don't think it will be fast enough to track all the information from a guitar?

PM: I don't think so, no. I'll be curious to see. Doesn't the 700 have it? (Editor's note: MIDI transmits 1040 30 bit "words" per second. See the Understanding Technology article in this issue for the answers to Metheny's questions.)

RUG: Yes the 700 does, and the idea behind it, of course, is that any MIDI instrument will be able to interface with any other digital equipment available, including other computers.

PM: I hope it works. It's hard for me to imagine how it could work and also get the dynamics. I could see how you could turn notes on and off, but when you bend a note or when you play with dynamics, you increase the amount of information that needs to be read by about ten times.

RUG: Beyond the Synclavier, what instruments are you using?

PM: Well, I'm using the Roland GR-300, which I love, and in fact, I'm amazed that more people aren't playing it. It's been like four years now, and I figured...when I went into a music store and played that, I said, "Man, I want to make a record quick, because everybody is gonna play this constantly on every record made from now on." And at this point, there are only three or four people who are really using it.

RUG: Who do you suppose that is?

PM: I don't know. I think that there's a kind of fear in guitar players. That's the only thing that I can figure out, that it's a fear of the unknown or something. I don't know if it's that or if it's intimidating or maybe they just like the sound of the guitar, they don't want to mess with it.

RUG: Could the boundaries between guitars and keyboards become less defined?

PM: I think that could be part of it, but I'll tell you what I think it is as much as anything, a lot of people still don't know what it means. I still have people come up to me, guitar players, after concerts, after I've played a screaming solo on the Roland, and they'll say, "God, how do you make your guitar sound like that?" and, I mean, it's up an octave, it doesn't sound anything like a guitar, it couldn't be anything but a guitar synthesizer, but because you're a guitar player standing there playing a guitar, they still perceive it as a guitar. So I think a lot of it is just lack of exposure.

RUG: Education?

PM: Yeah, maybe. And in fact the people that are using the Roland, most of them aren't really using it for what it can do. The only guy I've heard who really is exploring it is Adrian Belew and he's really dealing on it. I saw him play live and it was like, "yeah", he was tearin' it up. A lot of guys just turn it on and then open the filter and then close it and that's kind of it. But to me, the fact that it allows you to get to those other registers...obviously, you can tell from my records that I prefer getting the guitar up an octave, which I use the Roland for a lot. You get out of the tenor range and into the alto range, which is great.

RUG: So, is the guitar synthesizer the future?

PM: Ahh...not exactly. I think the future is always going to be good music and good tunes. And after messing around and spending, I don't know how many tens of thousands of dollars on all this junk, still find that if I write a good tune, it doesn't matter if I play it on the Synclavier, the Roland or a kazoo, if it's a good tune, it's gonna sound good on any of those instruments. So I think that the future is still in the hands of the composers and musicians who come up with the goods. But I do think that as far as stimulating the imagination, these instruments are incredible breakthroughs. There's music that I never would have played if I had not had the Roland, and that's pretty exciting right there, that an instrument can inspire you.

RUG:, How is a small town boy, not yet 30, affected by international success?

PM: Well, it's not really different. I mean, the only time that there was a real change for me around the time that the white Pat Metheny Group album came out, which is my third record and the first group album. Prior to that time, my idea of success was to be able to play a club with Gary Burton and have it half full on week nights and sold out on weekends. To me, that was about as big as it got in jazz, and when I made the decision to start my own group, I had been playing with Gary about three years and it was getting to be time to move on and think about doing something else. I had met Lyle and we had hit it off and we had fun playing together, so I said, "Well, let's try this," and we got some gigs. I had already won a couple of small polls in Downbeat magazine, you know, the "Talent Deserving Wider Recognition," I had a little bit of a reputation and I had those two records out, Watercolors and Bright Size Life. And we started the group and went out on the road and then that group album came out and all of a sudden, instead of selling 10,000 copies, it sold over 100,000 copies very quickly and that was a shock to me. And for a period of a year and a half or two years after that, I was kind of confused and you can hear it in American Garage and New Chataqua. Not so much, New Chataqua, that was made even before the group record came out, but especially American Garage. Of all the records, it's my least favorite and to me the weakest one. Because at the time, I figured I was a jazz guy and here we were selling all those records and having all these people come and I didn't know exactly why. And after a short amount of time, about a year of not exactly knowing what was going on, I just figured out, that all I really wanted to do and all that I had done up to that point was play the stuff that I liked. And when I resolved that question, everything became very easy. I was never interested in being in show business or being a celebrity or selling lots of records. All I ever wanted to do was be a musician and try to play the music that I like the best that I could play it. And that's all I do now. I use that as my saying, each day when I get up, I just want to play some stuff that I like and, I hope other people will like it too. But if they don't, that's OK. And I'm finding that my tastes as a listener are actually similar to a lot of other people's tastes. And on one level, I love hearing real simple pop music but on another level, I can listen to Ornette Coleman records all day long. And I hope I'll play music that conveys the love that I feel for all different kinds of music and, hopefully, it will always sound like me, too. So, as soon as I resolved that, everything was cool and there's nothing really to be changed, except that the only real change is that I can play a lot better now than a long time ago—and for some people that results in overconfidence. But I know that I play a lot better now than I did five years ago but I also know that five years from now, I'm going to play a lot better than I do now. And if you keep both those things in mind, it keeps you humble, in a way. Because you can see that it's a very transient experience, it's something you can't hang on to. If you say, "Gee, I'm really good and I play my ass off," the moment you start doing that is the moment you won't get any better, and I've never given in to that feeling. I always assume I should have done better. You can go too far with that, too, but so far it's worked for me in keeping everything in perspective.

RUG: I guess that's why those albums just keep getting better and better.

PM: Wait'll you hear the next one! Actually, there's two in the can right now. There's one that will be out this summer, I'm real proud of. It's different than the group thing, it's not a group record. It's me and Charlie Haden and Billy Higgins. The first side is all other people's music, three Ornette Coleman tunes, a tune by Horace Silver and a tune that Charlie wrote. And the second side is a couple of my tunes, one of which is really set up for a lot of improvising. And it's nice, I really like it. The album is called "Rejoicing". And after that, in September, there's a group record that we just did a couple weeks ago. It's...it's the BEST experience of my life, captured on a record. I mean, it's one of those things were we went into a studio for four days and everything worked. I mean, it's the best tunes that we've come up with, it's the new group, we've got a fantastic new drummer named Paul Wertico, and a great new utility musician, he plays guitar, he sings and he plays bass, he plays percussion, he's incredible, he's from Argentina, his name is Pedro Aznar. The album features both those guys quite heavily, and of course, Lyle and Steve Rodby, too. So, if the best record I've made up to this point scored a 30, then this record scored 100. I still can't believe that we got it in the can. It's not titled yet.

RUG: Where did you record it?

PM: In New York, at the Power Station.

RUG: With Manfred Eicher?

PM: No, this one I produced. But also on this record, it's probably going to be the first one that really features the Roland guitar with the Synclavier. There are three tunes where it's very prominent.

RUG: What about the future of the Pat Metheny sound, more synthesizer based music?

PM: Yeah, I think soon, sometime within the next year, I'm going to have to do a solo record just with the digital guitar and in fact, I won't have to go into the studio to do it. I can do it right here, on the floppy disc.

RUG: You can 'phone in your part'?

PM: Just about. In fact that's not far away at all. They've already talking about hooking up modems between the factory and some of the users in order to transfer discs, and if you can do that, it's literally phoning in your part.

Copyright © 1984 Roland Corp US